Thursday, July 3, 2025

When Ontario’s Blue Box household recycling initiative was launched in the 1980s it was lauded as being at least one of the major answers to the problem of plastic waste. Today one can find at least as many articles claiming that recycling is part of the problem while others insist that it is part of the solution. The term “Circular Economy” is often cited as part of the solution but what it means is often misrepresented as just another phrase to describe recycling.

The size and scope of the plastic pollution problem has magnified enormously with the major focus today apparently being that of microplastics, to be found in all major water bodies of the world as well as in the tissues of animals and plants from Pole to Pole and everywhere in between. It is difficult to know which sources of information to believe as well as which to dismiss as greenwashing or deliberate introduction of confusion by industry to discourage anti-plastic regulations that at a minimum would decrease plastic industry profits.

What we know is that the issue of microplastics is a serious environmental problem worthy of urgent study and development of policy solutions. Microplastics themselves have adverse ecological impacts and pose a risk to the health of living organisms including human beings, but the extent of the risk is still insufficiently researched and the industry research that does exist is not always published.

Plastic is an important component of aquatic and terrestrial litter but the extent of the environmental consequences of litter, as compared to the visual aspects of litter, is mostly unknown.

A recent UNEP-IUCN report identifies single use packaging not only that related to food, tires, textiles, abrasive particles added to personal care products, accidentally lost plastics such as fishing gear and primary pellets lost at sea, and products from almost all other industry sectors such as packaging, automotive, construction, electrical and electronics, medical, agriculture, and tourism, as contributors to the microplastics problem.

Many, but by no means all, single use plastic items help reduce waste and disposal of other materials such as food waste. Replacement of single use plastic items with reusable plastic items that almost always contain more plastic than the single use item, makes environmental sense only if the reusable items can survive many cycles of reuse without generating microplastics or reaching their own end of life.

There are many information gaps that need to be addressed just as there are many kinds of plastic in many gazillions of applications. To provide a comprehensive science based assessment of ecological impact, each resin type and each application needs to be assessed by scientists who understand the intricacies of Life Cycle Assessment and environmental toxicology. Few of those who comment about plastics in the popular press have this expertise so the information transmitted to users of plastic goods and packaging is often inaccurate or at least insufficient for making informed decisions.

Circular systems and sustainable projects

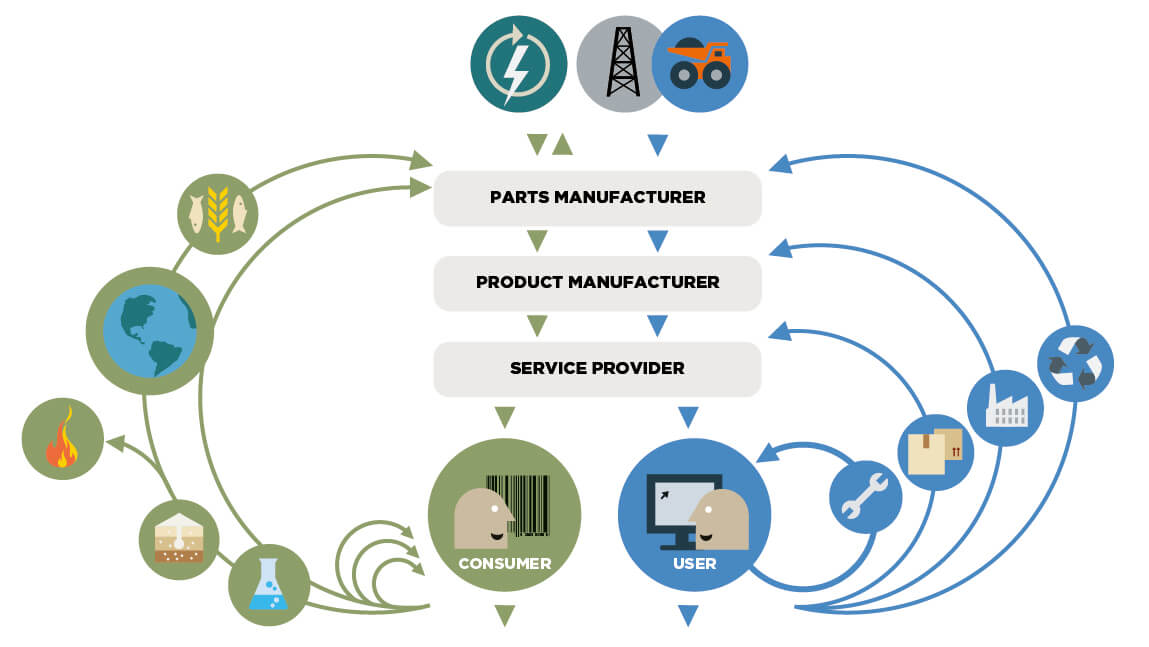

The answer to these conundrums almost certainly lies not just in more recycling but in adoption of a Circular Economy, defined by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation as “a system where materials never become waste and nature is regenerated. In a circular economy, products and materials are kept in circulation through processes like maintenance, reuse, refurbishment, remanufacture, recycling, and composting. The circular economy tackles climate change and other global challenges, like biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution, by decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources.”

The Circular Economy, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

The Foundation’s work advocates the that “through design, we can eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials, and regenerate nature, creating an economy that benefits people, business and the natural world.”

According to the foundation’s research, a circular economy for plastic would achieve the following: Eliminate the plastics we don’t need; innovate to ensure that the plastics we do need are reusable, recyclable, or compostable; and, circulate all the plastic items we use to keep them in the economy and out of the environment.

Furthermore, the foundation is calling for a circular economy system by 2040, which has the potential to:

reduce the annual volume of plastics entering our water by 80 per cent

reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25 per cent

generate savings of USD$200 billion per year

create 700,000 net additional jobs

A Circular Economy for plastics alone risks transferring the environmental challenge from plastics to other materials. It is becoming abundantly clear that a Circular Economy for everything is the only environmentally sensible way for humankind to achieve sustainability of our global home.

![]()

Colin Isaacs is a chemist with practical experience in administration, municipal council, the Ontario Legislature, a major environmental group, and, for the past three decades, as an adviser to business and government. He is one of the pioneers in promoting the concept of sustainable development for business in Canada and has written extensively on the topic in the popular press and for environment and business platforms.

Featured image credit: Getty Images