Monday, June 30, 2025

Buildings are one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Canada, and circularity strategies – such as design for flexible use, retrofit and upcycling, and more – can help extend the life of buildings and preserve embodied carbon in the process.

With this in mind, Environment Journal was invited to an informative webinar on applying circular economy strategies to extend the life of existing office buildings, co-hosted by Circular Economy Leadership Canada (CELC) and CSA Group.

Helen Goodland, an architect with Scius Advisory, and Ryan Zizzo, a professional engineer and CEO of Mantle Developments, took the opportunity to present findings from two research reports published by CSA Group (available here and here) that provide new guidance for industry on circular strategies for Canada’s real estate and construction sectors.

“With the dramatic increase increase in office retrofits since the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with emerging environmental policy and investor priorities, now is the time to seize the opportunity to apply circular economy strategies in the sector,” said Goodland, who provided an overview on the first report, entitled “Advancing Circular Economy Strategy for Existing Buildings in Canada.”

Developed by Scius Advisory, in collaboration with Circular Economy Leadership Canada (CELC) and a number of partners from industry and government, the guide was informed by research and consultation with a number of leading real estate owners, designers, and builders from across Canada and around the world, drawing from the two technical reports published by CSA Group with respect to opportunities for applying circular strategies to existing buildings.

The guide is designed for industry and organized inline with circular economy strategies that can be applied by Canada’s commercial real estate sector, including concepts and practices such net zero design, design for flexible and adaptable use, durability, zero waste construction, innovative leasing, and deconstruction. It presents current methods and examples (i.e., case studies) of these strategies and practices being applied within the Canadian and global commercial office market, highlighting actions that building owners, developers, property / asset managers, designers, and builders can implement.

It also offers a selection of tools and resources to help get started, including important considerations when deciding whether to demolish and build new, or explore creative strategies that extend the life of existing buildings (and preserve their embodied carbon in the process).

According to Goodland, this guide is particularly relevant to office buildings, but she also notes that many, if not all, of the circular strategies described are applicable to other building types.

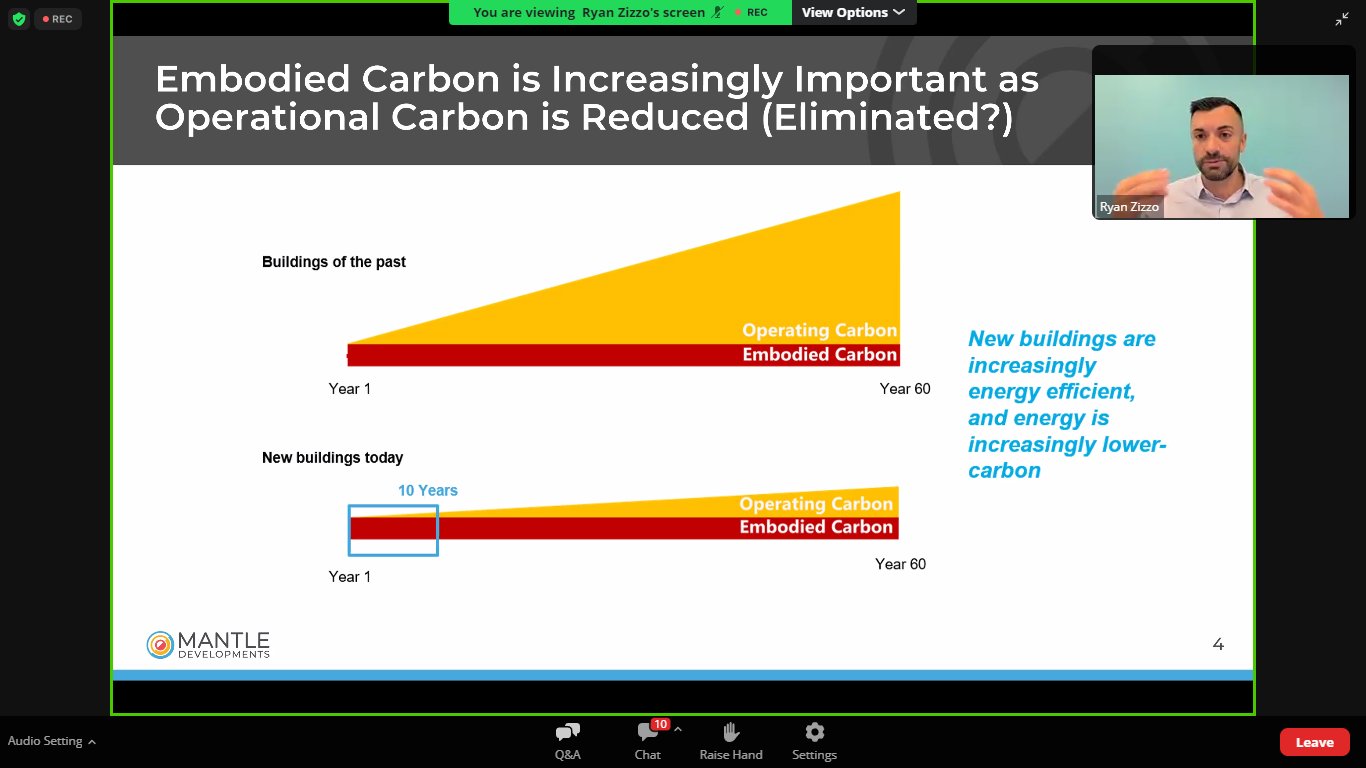

Zizzo delved into the highlights of the second report, which is focused on an investment landscape informed by climate-related risks, the emphasis in the commercial real estate sector on developing new buildings increasingly conflicts with achieving GHG emission reduction targets.

“Looking at these critical years leading toward net zero targets, new buildings are increasingly energy efficient and energy is increasingly lower-carbon out of necessity,” emphasized out Zizzo.

According to this report, even constructing the most energy-efficient building entails variable but significant upfront GHG emissions because of the resource-intensive nature of construction and the materials supply chain. Extending the life of buildings through retrofit, repair, maintenance, and adaptive reuse is a key principle of the “circular economy”. The circular economy proposes an alternative to the linear system of production and consumption characterized by “take-make-use-dispose”. This restorative and regenerative system minimizes resource use, waste, and emissions by narrowing (efficient resource use), slowing (temporally extended use), and closing (cycling) material loops.

This report provides guidance and best practices on extending the lives of existing office buildings by looking, in turn, at:

(a) the design interventions that could optimize an existing building for ongoing operations while improving the potential for future renovations;

(b) the ways to minimize waste generated from maintenance and renovation activities and, ultimately, end of life; and

(c) construction material flows and incorporation of salvaged materials into projects.

According to the research, many circular strategies are not new in Canada, but are undertaken on an ad hoc basis. Underutilized approaches such as embedding life cycle thinking into real estate decision-making, the use of digital technologies, and innovative leasing structures are ways for industry to get started on the journey to a circular economy for office buildings. These approaches make it easier for owners to include building reuse as an option for their office properties, stimulating demand for industry training programs and secondary materials markets – which exist, but not at sufficient scale.

This report also reviews a number of policies, financial measures, and voluntary programs in place in Canada that help to extend the lives of existing office buildings. Numerous models from other jurisdictions could be applied to the Canadian context to help fill gaps.

Standardization is necessary to ensure that the information and practices associated with products and buildings are consistently and accurately calculated and presented. Standards underpin building codes, but the standards landscape in Canada is underdeveloped when it comes to existing buildings and the circular economy. At the most elementary level, terms such as “restoration”, “retrofit”, “renovation”, “alteration”, “refurbishment”, and “renewal” are all used interchangeably when, in fact, they mean different things.

Research for this report uncovered gaps in local and regional policies, zoning, land use and development bylaws, and building regulations; data collection and management (for existing buildings and at the industry scale for benchmarks such as life cycle costing and life cycle assessment); building information modelling standards for existing buildings; procurement standards that promote a “renovation first” approach; documentation and certification of used materials, building adaptability information and disclosure; insurance and risk management; and industry training curricula and professional accreditation.

The data indicates that applying circular economy principles to Canada’s real estate and construction sectors could deliver multiple benefits, including:

- creating new economic, investment, and employment opportunities;

- reducing waste and GHG emissions;

- enhancing natural ecosystems and urban green spaces;

- improving the resilience of supply chains; and

- providing greater equity and related social benefits.

Inevitably, there are economic and environmental trade-offs and these need to be managed through the use of consensus-based analytical methods (such as life cycle costing and life cycle assessment) based on industry-accepted data.

A growing number of exemplary projects in Canada and around the world included in this report illustrate how successful renovation and adaptive reuse can maintain the functional viability of an office building while achieving economic efficiency. They offer examples for industry to build technical knowledge and for policymakers and owners to consider renovation instead of demolition for underperforming office buildings.

An industry panel also provided context for the reports and these important issues impacting the construction and real estate sectors.

“We can see a sort of train crash ahead of us in certain city centres,” said Enlai Hooi, head of Innovation at Schmidt Hammer Lassen (SHL) Architects. “We have to provide a hardcore business case for how these buildings can be transformed.”

Hooi is an architect and industrial designer specialising in the integration of engineering fields within circular design and architecture who leads the SHL’s sustainability approach in competitions and develops thought leadership on the topics of adaptive transformation in architecture, circular construction methods, materials health and change management. His projects include the integration of circular design and engineering systems into architecture, adaptive recycling, master plans and the development of a range of patented architectural products that contribute to the sustainable performance of buildings. Enlai has won a number of awards in both architecture and design.

“We have to frame things within the framework of circularity,” he said, emphasizing that “transformations are usually cheaper than building new” and that it’s important to calculate the margin of error and to calculate risks while being imaginative. Hooi pointed out that the cost of transformation is primarily in labour and for a new build it’s primarily in building materials, which often times comes from abroad. “Labour is usually localized and therefore a win for local economies.”

Hazel Sutton, the director of Sustainability for the Property and Asset Management group at JLL, a global real estate services firm specializing in commercial property and investment management, also shared her experienced perspectives.

“We are the boots on the ground, in the buildings, having discussions with the asset managers” said Sutton, who is busy making the business case for circular procurement. “The business case exists and what we need to do now is keep repeating it.”

For more than a decade, she has worked with NGOs, government, and the commercial real estate industry to improve the environmental, social, and economic performance of real estate assets. With an emphasis on fostering a collaborative environment across stakeholder groups, her work is focused on identifying strategies and programs that will provide long-term value to building managers and owners.

“If we all help accelerate the message then there’s a trickle down effect to other companies,” she says. “We need to come together to continue to refine relationships and work with construction services teams and procurement teams so that we can make it business as usual and cementing the buy in about futureproofing our buildings.”

As the VP of Climate and Sustainability for EllisDon Corporation, Jolene McLaughlin works to build partnerships across the industry to support climate mitigation and adaptation strategies in the build environment. She has spent more than 12 years driving sustainability initiatives across various segments of the built environment from concept into execution. Working with project teams with a collaborative approach, in support of the identification, definition and implementation of practical strategies that result in more efficient, resilient and comfortable buildings.

“In terms of office to residential conversion programs, it’s important to provide an efficient site layout, vertical integration and the design is sufficient for changing occupancy types in future,” said McLaughlin, who said municipal incentive programs are helpful to accelerate progress.

Another useful resource mentioned at the webinar was CircularProcurement.ca, a first-of-its-kind Canadian resource and initiative of the Circular Innovation Council to support Canada’s collective understanding of the circular economy and how purchasing advances it. Through knowledge exchange and collaboration CircularProcurement.ca is a leading showcase of insight and experience to put circular economy concepts into action.